A Brilliant Light

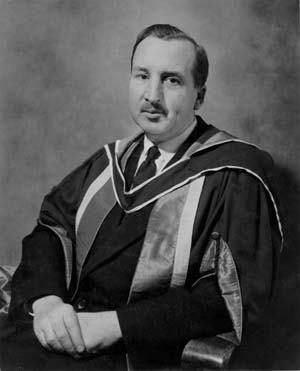

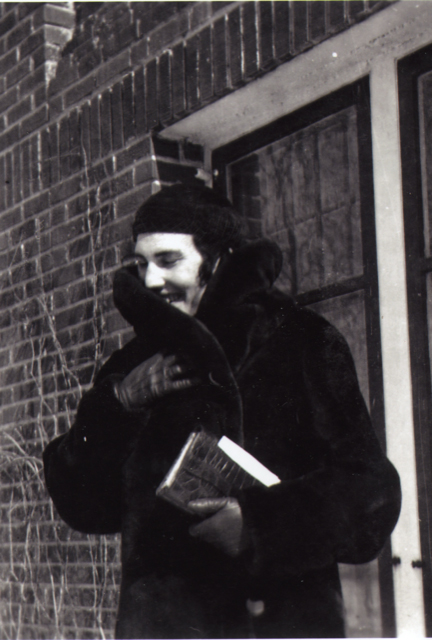

Gerhard Herzberg at University of Saskatchewan

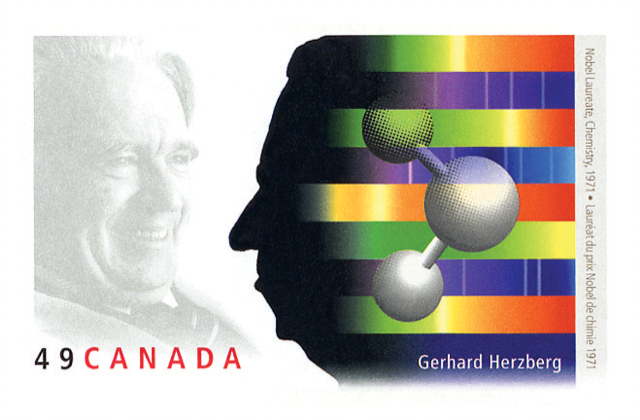

In Nov. 1971, spectroscopist Gerhard Herzberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "his contributions to the knowledge of electronic structure and geometry of molecules, particularly free radicals."

Herzberg's path to the Nobel and a storied career as one of Canada's most brilliant minds was made possible thanks to University of Saskatchewan which welcomed him to Canada in 1935. His accomplishments at USask and at the National Research Council continue to light the path for scientific endeavours today.

Photo Credit: NRC

Celebrating USask’s Nobel Laureate Gerhard Herzberg:

A legacy in unravelling the mysteries of the microscopic world

by Kathryn Warden, first published in USask's Green & White, Aug. 2021.

When Gerhard Herzberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry 50 years ago for ground-breaking discoveries in a lifelong exploration of the structure of matter, he publicly thanked the University of Saskatchewan.

“It is obvious that the work that has earned me the Nobel Prize was not done without a great deal of help,” Herzberg said in his acceptance speech, acknowledging “the full and understanding support” of successive USask presidents and faculty who “did their utmost to make it possible for me to proceed with my scientific work.”

"He was certainly a pioneer"

Herzberg’s brilliance in studying the spectra of atoms and molecules to understand their physical properties significantly advanced astronomy, chemistry and physics—enhancing knowledge of the atmospheres of stars and planets and determining the existence of some molecules never before imagined.

“He was certainly a pioneer,” said USask PhD student Natasha Vetter, winner of both the 2014 Herzberg Scholarship and the 2018 Herzberg Fellowship. “Without his work, the fundamental tools we use as chemists and biochemists wouldn’t exist. I feel pretty honoured to be part of that legacy and to have received those awards.”

While at USask from 1935 to 1945, Herzberg made discoveries that laid the groundwork for his work at Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory and then at the National Research Council (NRC), culminating in his celebrated work on free radicals—highly unstable, short-lived molecules that are everywhere: in our bodies, in materials and in space. They help important reactions take place but an imbalance can cause damage such as cancer or age-related illness. Knowledge of their structure is now used to make pharmaceuticals, medical radiation tests, light sensors, and a wide range of innovative materials.

"Much that we have developed today would not have been discovered if Herzberg hadn’t done this fundamental research.

“This was the beginning of molecular spectroscopy, and it was an exciting time because it was all so new,” said Alexander Moewes, Canada Research Chair in Materials Science with Synchrotron Radiation.

“Herzberg was unravelling the structure of molecules, specifically free radicals. Many of today’s drugs and human biochemistry processes are governed by these molecules. So much that we have developed today would not have been discovered if Herzberg hadn’t done this fundamental research. This can’t be overstated.”

But Herzberg’s story is not one of the “lone genius.” In a 1984 speech, he singled out 11 Canadians who had been critical to his success. Half had connections to USask. Two were former USask presidents: Walter Murray and John Spinks whom Herzberg credited with providing him “a haven and safety from the Nazis.”

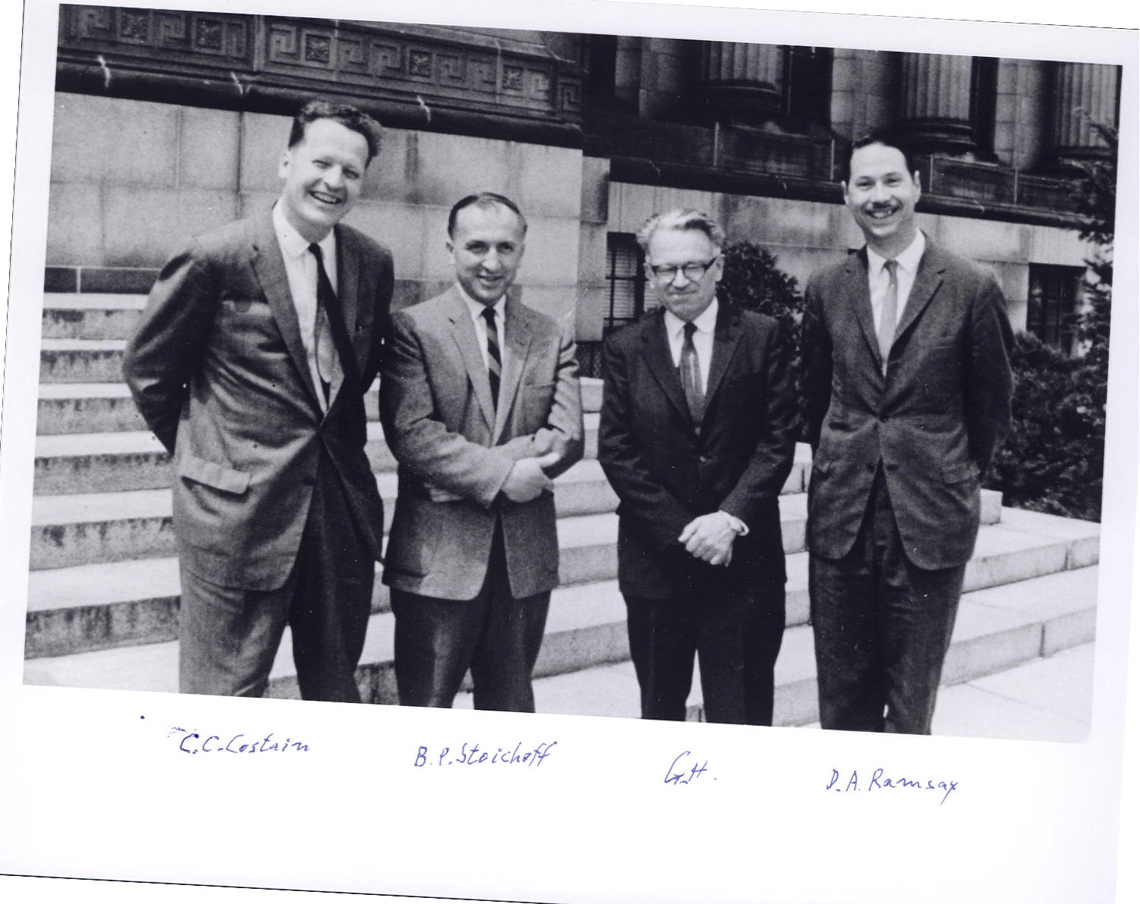

Two were USask alumni who were NRC presidents during Herzberg’s 46 years there—C.J. Mackenzie and Bill Schneider. Another was Herzberg’s master’s student—Alex Douglas—who went on to work closely with Herzberg for many years at the NRC. Also cited was Herzberg’s long-time NRC research colleague Boris Stoicheff (father of President Peter Stoicheff) who became Herzberg’s biographer.

And this list scarcely captures the disproportionate role that USask leaders, researchers and alumni played in Herzberg’s story—one that has had a lasting impact on science globally, on Canadian science policy, and even on the building of Canada’s only synchrotron at USask where today scientists from across Canada and around the world continue to unravel the mysteries of atomic and molecular structure.

“It’s a story of courageous curiosity and collaboration that brought Canadian science to international prominence and has a continuing legacy today,” said President Stoicheff.

Coming to Canada

How did a renowned German scientist on track before he was 30 to become a world leader in mapping the structure of molecules end up at a far-flung Canadian prairie university?

The story begins with the confluence of two widely separated historical events—desperate financial straits at USask during the Great Depression and the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany.

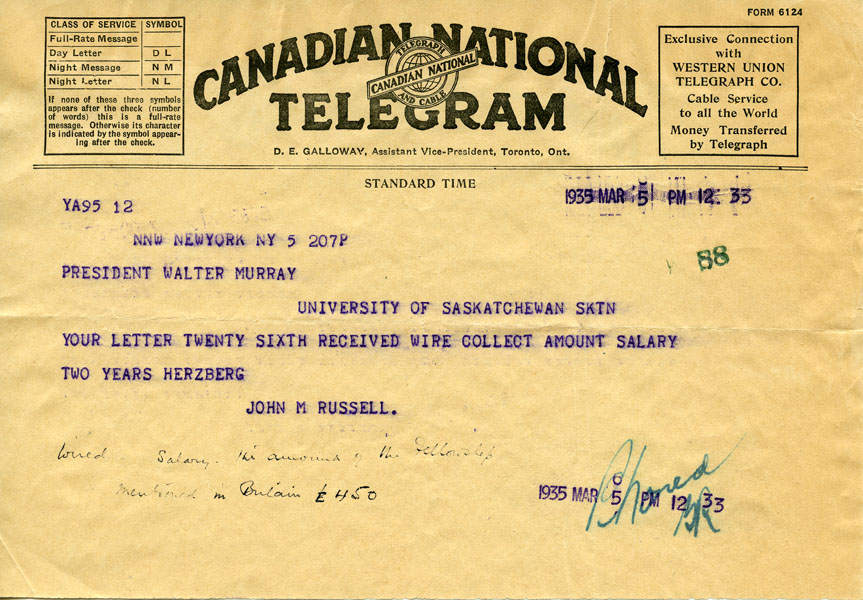

When the crops were so bad that many students couldn’t pay tuition, USask gave unmarried faculty a year off in 1933. John Spinks found a position at Herzberg’s already renowned lab in Germany. Spinks lived in the same Darmstadt rooming house as Herzberg and his wife Luise, also a spectroscopy scientist. They became fast friends.

But after Spinks returned to Saskatoon, the young couple found it impossible to live under the Hitler regime. As part of the Nazi purge of universities, Herzberg was denied the right to teach because his wife Luise was Jewish.

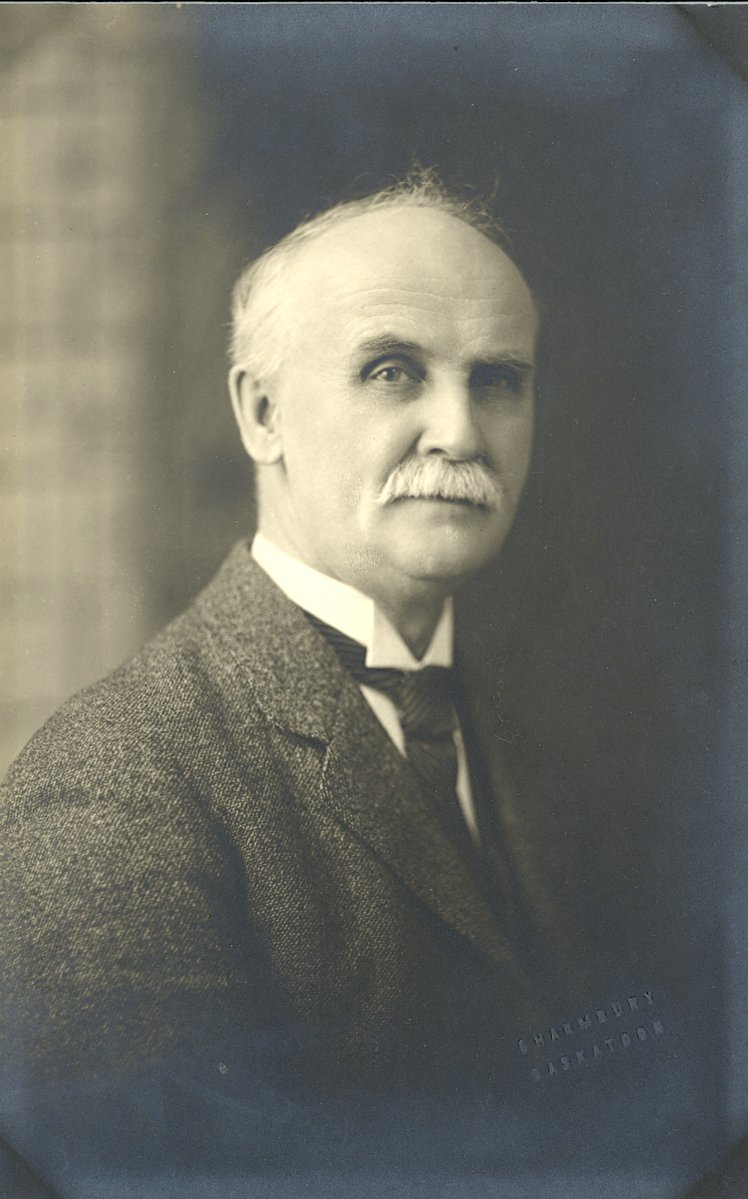

Herzberg appealed to universities in Europe and Canada, but none were able or willing to assist. Spinks raised the issue with then USask President Murray who saw an opportunity to help a refugee couple and build Canadian research. He eventually arranged a Carnegie Corporation guest professorship at USask—despite the lack of suitable research equipment and advanced graduate students (master’s was the highest degree).

Gerhard and Luise Herzberg arrived at USask in 1935.

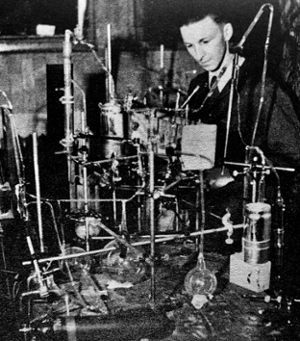

The Herzbergs arrived in Saskatoon with $2.50 and some optical equipment, including special infrared plates, to build a prism spectrograph, “If the Nazis had known that, they probably would have smashed the plates,” Herzberg later remarked. Herzberg became a lifelong friend of physics department head Ertle Harrington whose expert glass blowing skills were enlisted, along with staffer Bert Cox’s instrument-making expertise, to help build the specialized equipment.

With fewer than 3,000 students and about 100 faculty, Herzberg described USask as “a nice small university” with “remarkably high” standards, a place where you “soon learned to know every one of the faculty members, whether it was in science or the humanities.”

Herzberg taught two classes and published 20 papers in his first four years. With Luise’s help, he wrote three of his six books that have become standard texts in the field. One, translated into English by Spinks, was dedicated to President Murray.

In 1941, Herzberg and student Douglas identified the presence of the methylene ion CH₂+ in space, a discovery covered by the New York Times. Though they didn’t accurately identify the spectra of free methylene radical CH₂ until 1959 at the NRC, the quest for it began with a USask experiment to confirm the molecule’s existence in a comet spectrum.

“You’d be walking downtown and hear a whoomp! from the university campus and you knew it was Herzberg.”

Herzberg also worked on the spectra of explosives using a small earthen detonation hut behind the Physics building, often creating loud explosions. “It was a feature of day-to-day life in Saskatoon,” recalls former student Bill Cameron. “You’d be walking downtown and hear a whoomp! from the university campus and you knew it was Herzberg.”

Herzberg described his time at USask as “the 10 best years” of his life, according to his daughter Agnes, a renowned statistician, USask alumna, and honorary degree recipient.

Luise’s friend Hildred Rawson, wife of biology professor Donald Rawson after whom Rawson Lake in the Rockies is named, wrote that the Herzbergs “very much loved in Saskatoon” and that “their wish to know us and to be one with us in our ambition to make something of our little community was heartwarming.”

The Herzbergs joined artist Ernest Lindner’s Saturday night discussion gatherings of local journalists, teachers, artists and professors. Businessman and art lover Fred Mendel was also a friend. Herzberg, who had a strong bass-baritone voice and loved opera and lieder, took singing lessons in Saskatoon.

Known for his humanity, humility, and humour, Herzberg made visits back to Saskatoon including a post-Nobel Prize visit where, to his great delight, the Intensely Vigorous College Nine band serenaded him with "Oh You Doll, You Great Big Beautiful Doll.”

USask alumnus Benoit Simard (PhD'87), whose career at the NRC overlapped for many years with Herzberg’s, remembers the day Herzberg came to class.

“It was amazing,” recalls Simard. “We knew about him through the courses we were taking. We had a little time to talk to him briefly and he signed my copies of his books. He was a great person. He found interest in what you were doing and paid attention to it.”

USask Herzberg student Cec Costain, who later joined Herzberg’s NRC lab, remarked that Herzberg “made scientists of us farm boys.” Herzberg’s students ended up in laboratories and observatories in many countries.

Among them were Henry Taube (1983 Nobel Prize winner) and Bill Schneider who were from neighbouring farms and roomed together. Schneider became a pioneer in nuclear magnetic resonance, paving the way for MRI scans today. As NRC president, Schneider oversaw creation of the NRC Plant Biotechnology Institute on campus. Student Lorne Gray, who drafted illustrative figures for Herzberg, later became Atomic Energy of Canada president.

“He brought a level of excellence in basic fundamental physical science to this university that this university had not seen previously,”

Professor Emeritus Ron Steer says Herzberg’s decade at USask boosted the importance of scientific research on campus.

“He brought a level of excellence in basic fundamental physical science to this university that this university had not seen previously,” said Steer. “His longstanding influence has been that USask has in many respects blossomed in many different disciplines—and also from the linear accelerator leading to the CLS—that otherwise might not have happened at all.”

The serendipitous Spinks-Herzberg meeting and Herzberg’s subsequent hiring were arguably the “most important events in eventually landing the CLS over 60 years later,” wrote former CLS director Michael Bancroft in a 2020 history of Canada’s synchrotron. Herzberg’s spectroscopic work, along with the first electron accelerator in Canada—the betatron used for cancer therapy and nuclear physics, paved the way for the CLS. “Everybody who uses the Canadian Light Source today is leaning on Herzberg,” said Moewes.

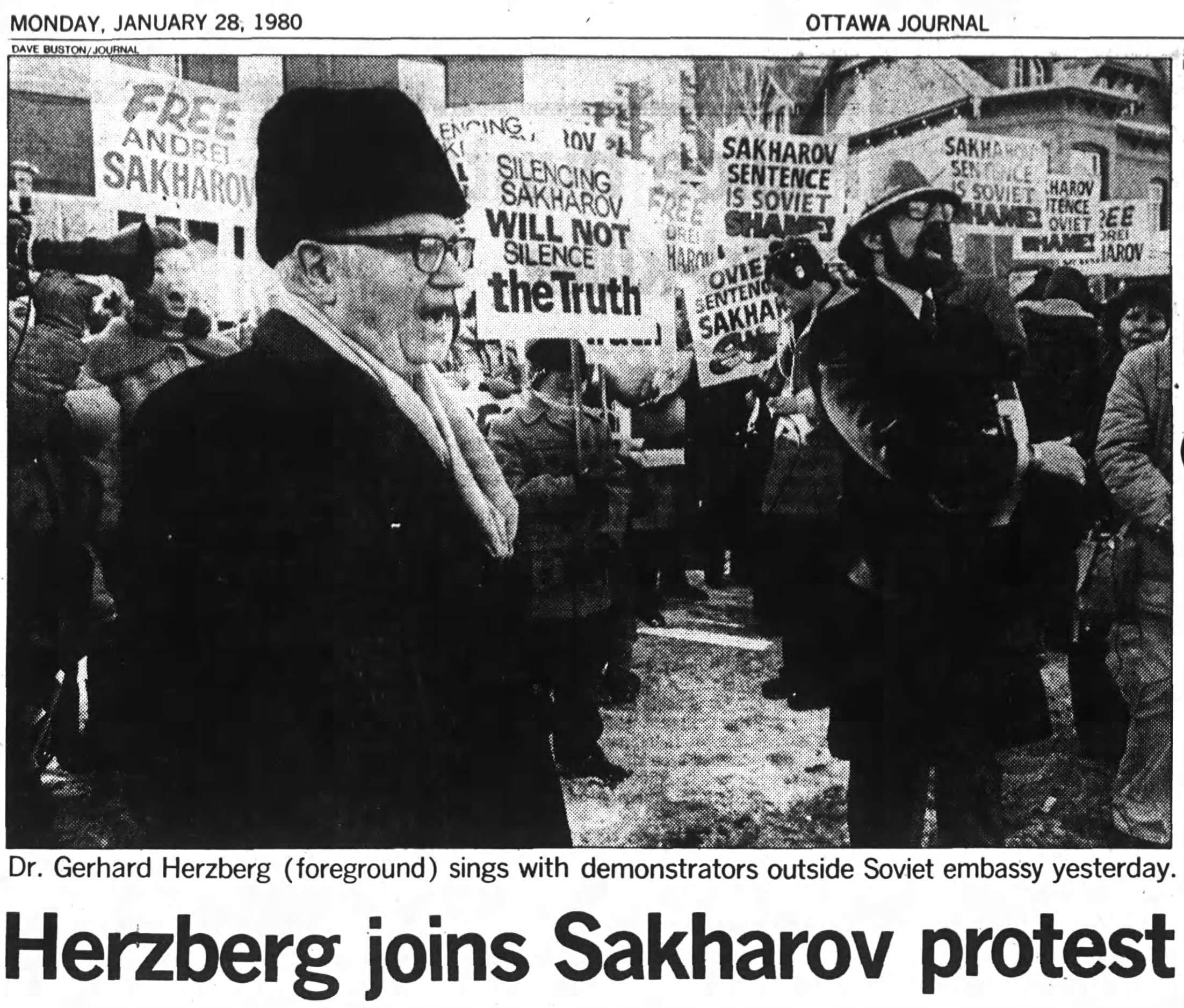

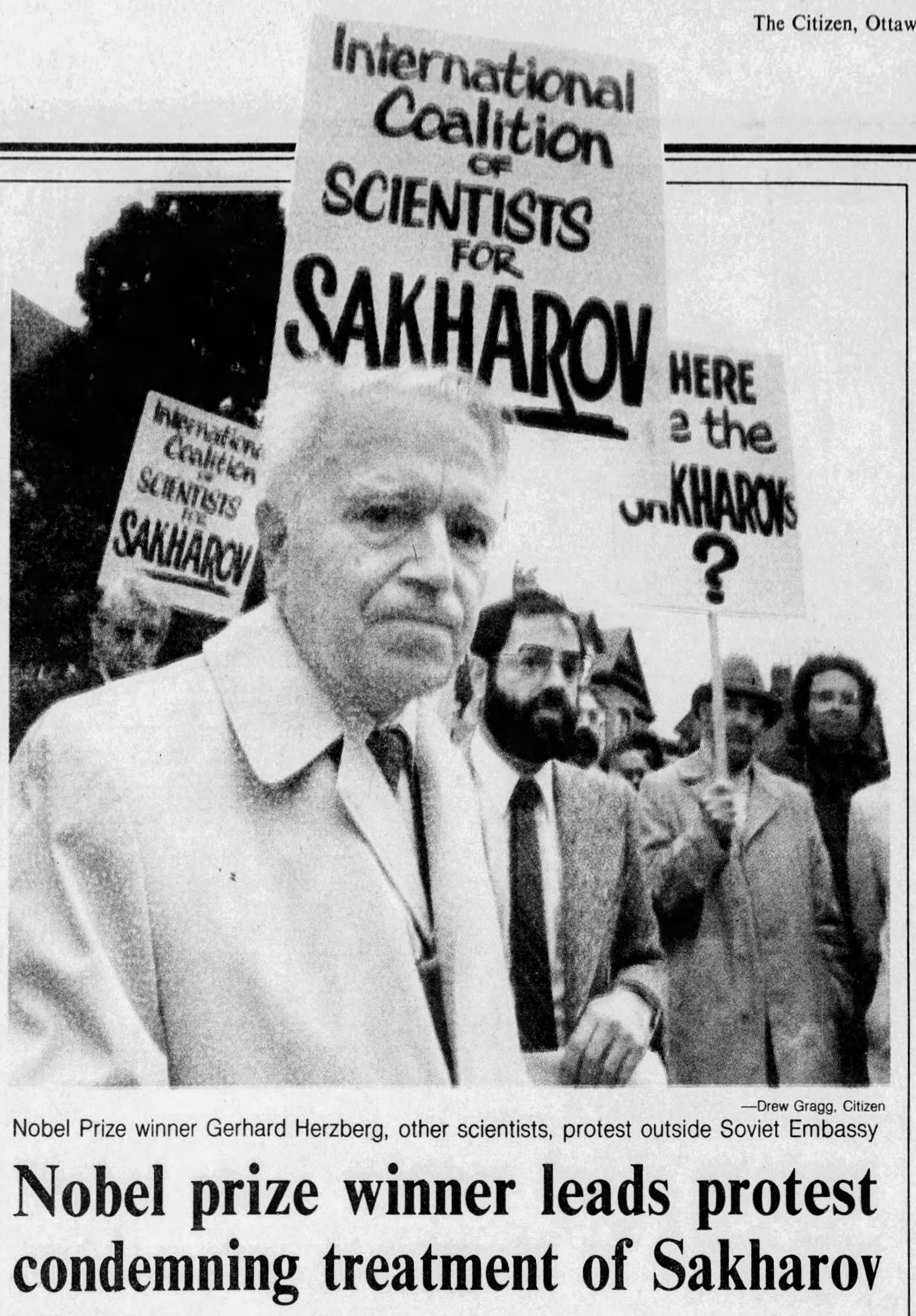

Awarded 37 honorary degrees, Herzberg used his Nobel Prize celebrity to protest Soviet oppression of intellectuals (twice he demonstrated outside the Soviet embassy in Ottawa) and to press for support for basic science, stressing no one can foresee the practical applications of pure research.

“Nobody would have ever discovered or invented the laser if it had been directed science,” he said. “It was not because somebody had the idea and told the scientists ‘You invent the laser.’”

At his 1999 memorial, Agnes recalled that her father “always listened and weighed the evidence”, highlighting this with a humorous story about his response when asked why he did not believe in God : G.H. (as he was known to friends and family) said that he had not seen enough data.”

“G.H. spent his life in the pursuit of science and the arts. He searched for openness, honesty and objectivity,” she said.

“We and the world should and will never forget G.H.”

Naming of Herzberg Experimental Hall

As part of a national initiative to mark the 50th anniversary of Gerhard Herzberg’s Nobel Prize, USask named the main experimental hall of the Canadian Light Source (CLS) and a prominent physics lecture theatre on campus after the renowned scientist.