Nobel Prize winning work

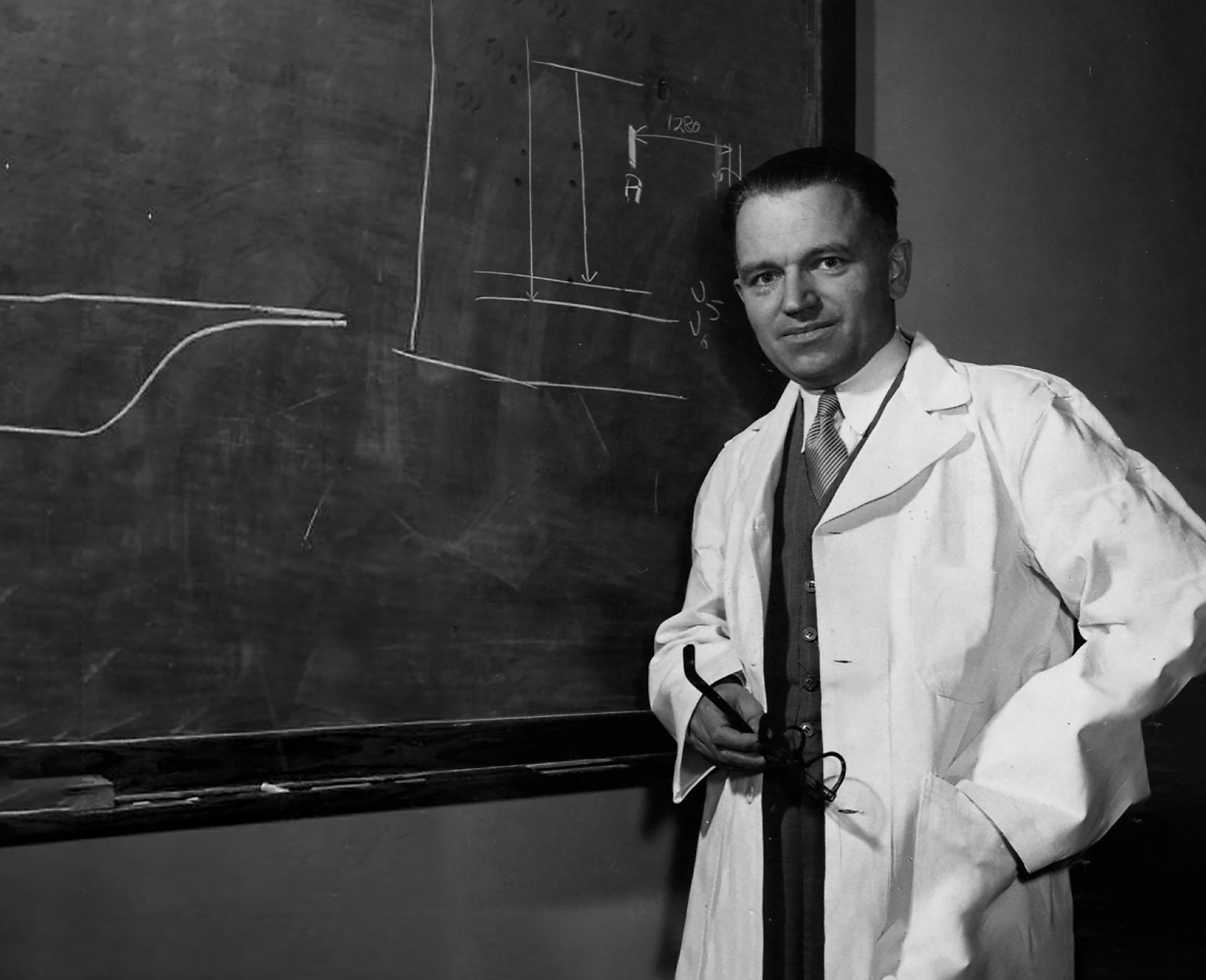

In Nov. 1971, spectroscopist Gerhard Herzberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "his contributions to the knowledge of electronic structure and geometry of molecules, particularly free radicals."

Herzberg's path to the Nobel and a storied career as one of Canada's most brilliant minds was made possible thanks to University of Saskatchewan which welcomed him to Canada in 1935. His accomplishments at USask and at the National Research Council continue to light the path for scientific endeavours today.

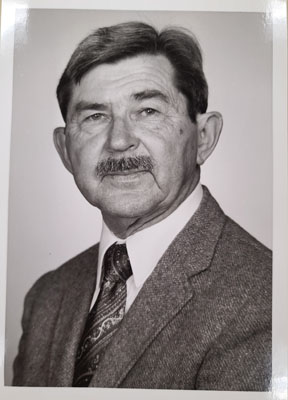

A second Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In 1983, Henry Taube was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry “for his work on the mechanisms of electron transfer reactions, especially in metal complexes”.

Born in 1915 in Neudorf, SK, the chemist was educated at USask, receiving a Bachelor of Sciences in 1935 and a Masters in Sciences in 1937.

He received his PhD from the University of California in 1940 and went on to teach at Berkely, Cornell and Stanford.

Taube is the only Saskatchewan-born Nobel laureate and, as of 2022, the only graduate of USask to win a Nobel Prize. He passed away on 16 November 16th, 2005.

Innovative nuclear medicine

![Sylvia Fedoruk treating a patient [Credit: University Archives, Harold Johns Collection]](https://research.usask.ca/images/about/legacy/johns_fedoruk_with_patient_1.jpg)

In 1951, University of Saskatchewan medical physicist Dr. Harold Johns and his graduate students became the first researchers in the world to successfully treat a cancer patient using cobalt-60 radiation therapy. This innovative technology—dubbed the “cobalt bomb” by the media—revolutionized cancer treatment and saved the lives of millions of cancer patients around the world.

Explore the WDM online exhibit “The Cancer Bomb”, the timeline of USask achievement in medical imaging, videos of the people who made this all happen, and stories about the exciting USask research that is carrying on this legacy.

Agtech research

USask is the centre of a growing agricultural technology hub that includes Canada’s only synchrotron, one of the world’s largest level 3 containment facilities for infectious disease research, and a unique “smart farming” laboratory for livestock and forage research, as well as federal and provincial labs focussed on agricultural innovation. By co-ordinating with our partners and collaborators, and sharing our state-of-the-art infrastructure capacity, USask is:

- Applying science and advanced technologies

- Increasing value through digital agricultural innovation

- Spanning the agricultural supply chain, not limited to one area or sector

- Focusing on global impact

- Adapting to climate change through agtech solutions

Researchers at USask's Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization-International Vaccine Centre (VIDO-InterVac) are making progress towards preventing and treating animal and human diseases of today—including COVID-19, Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Zika virus, African Swine Fever (ASF), and Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV)—and the emerging threats of the future.

Space research

The human body in space

Human beings living in space present unique challenges for human health -- we're engineering the medical tools that humans in zero gravity will need. In the zero gravity of prolonged space flights, astronauts suffer loss of muscle and bone mass that mimics osteoporosis.

To address this problem, a University of Saskatchewan research team is building a portable MRI scanning device to monitor astronauts’ muscle and bone health on space missions. With a Canadian Space Agency grant, researcher Gordon Sarty is designing and engineering an ankle-sized MRI device for the International Space Station (ISS) by the early 2020s. The device will weigh only 50 kilograms and will be able to provide images of muscle and bone using novel radio transmitter technology.

Understanding bone loss and recovery processes will have applications for osteoporosis treatment back on Earth. The new technology also holds great promise for improving the health of people in rural or remote areas who have little access to medical imaging, as well as for possible use in ambulances, dental clinics, and operating and emergency rooms.

The new MRI for the ISS will also demonstrate technologies needed to build an MRI for a moon base in the 2030s.

Optical Spectrograph and InfraRed Imaging System (OSIRIS) on Odin

USask technology can be seen in the night sky today.

OSIRIS is a critically important USask-designed and built satellite instrument, deployed and currently in operation aboard the Swedish Odin satellite. It's a collaboration with the Canadian Space Agency. The objective of the Odin mission is to provide new information on the extent to which humans are changing the atmospheric environment, specifically through the study of stratospheric and mesospheric ozone, focusing on the space between the highest mountains and the edge of space -- altitudes from seven to 90 km above the Earth.

Protein crystals in space

Space Weather: Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN)

What is a SuperDARN?

Pairs of high-frequency Doppler radars are used to measure geomagnetic conditions --ionospheric velocity, electric field patterns, and a map of voltage - using 15 radars across both the northern and southern hemispheres. That data is matched with information gathered by satellites about solar winds - geomagnetic energy fluctuations from the sun - 1.5 million kilometers away.

In principle, each radar pair can measure a region of the ionosphere over 3 million square kilometers in size, and can do this for 24 hours each day.

In January 2002, there were 15 operating radars, 9 in the northern and 6 in the southern hemisphere. Substantial funding has been provided for SuperDARN by Canada, the United States, France, Great Britain, Japan, South Africa, Australia, and Italy. The ISAS team controls the Saskatoon, Prince George, Rankin Inlet, Inuvik and Clyde River radars, whose partners are the US-run radars at Kapuskasing, Ontario, and Kodiak, Alaska, respectively.

USask Archives

Visit the link below to access the USask archives for more research history. Take a walk through time.